|

|

We’re drowning in trash. These

Dutch scientists have a solution.

August 23, 2018 4:39 am Published by VICTOR

TALAMANTES LEAVE YOUR THOUGHTS

ByRachel Nuwer

August 21

PETTEN, Netherlands — Hidden behind undulating sand dunes and fog

rolling off the North Sea, the sprawling, gated campus of the Energy

Research Center of the Netherlands (ECN) sits on a spit of land

about an hour north of Amsterdam. Crying gulls circled a building

crammed with pipes, machinery and scaffolding, while in a nearby

control room, engineers in yellow hardhats peered at a confounding

series of digital flowcharts and graphs. They were working on one of

clean energy’s intransigent problems: how to turn waste into

electricity without producing more waste.

Decades ago, scientists discovered that when heated to extreme

temperatures, wood and agricultural leftovers, as well as plastic

and textile waste, turn into a gas composed of underlying chemical

components. The resulting synthetic gas, or “syngas,” can be

harnessed as a power source, generating heat or electricity. But

gasified waste has serious shortcomings: it contains tars, which

CLOG engines and disrupt catalysts, breaking machinery, and in turn,

lowering efficiency and raising costs.

This is what the Dutch technology is designed to fix. The MILENA-OLGA

system, as they call it, is a revolutionary carbon-neutral energy

plant that turns waste into electricity with little or no harmful

byproducts. In the mid-1990s, Mark Overwijk, the director of the

ECN’s biomass and energy efficiency unit, and his colleagues set

their sights on solving the tar problem. They were years ahead of

their time. “Everyone was asking, ‘Why are these guys working on

biomass?’” Overwijk recalled to The WorldPost, referring to organic

material used as fuel. “We wanted to develop a technology to make

the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy possible in a

realistic way.”

The goal was to make gasification “the centerpiece of a new circular

economy,” Overwijk said. “One based not on fossil fuels, but on

biomass.”

Over the last 20 years, Overwijk and his colleagues have developed

and perfected their technology, running the machinery for over 8,000

hours, working out the kinks and ensuring it is well-suited for

processing everything from household rubbish and demolition debris

to century-old railroad ties, paper industry leftovers and tulip

bulb waste.

The MILENA-OLGA process, which heats garbage to over 1,300 degrees

Fahrenheit, is 11 percent more efficient than most existing

energy-from-waste plants and over 50 percent more efficient than

incinerators of a comparable scale. It’s also more environmentally

friendly. While the conversion from solid to gas does generate

carbon dioxide, because it offsets fossil fuel energy and does away

with landfills that would eventually produce methane, it is

ultimately carbon neutral or environmentally beneficial. The process

also emits zero wastewater and produces no particulates or other

pollutants. Just 4 percent of the original material is left over as

inert white ash, which can be used to make cement.

For now, MILENA-OLGA syngas is used to power the same sort of

turbines used for natural gas plants, but the ECN researchers have

bigger plans. They recently TEAMED UP with two of Europe’s largest

gas utility companies to demonstrate how their syngas can be

injected directly into the Dutch gas grid, and they are working on

synthesizing liquid chemicals in the lab. As its name implies,

syngas can be synthesized to make jet or diesel fuel or virtually

any of the THOUSANDS of things traditionally made with fossil fuels,

including plastics, clothing, cosmetics and computers. As Bram van

der Drift, one of the researchers who developed the technology, put

it: with a gaseous fuel now in hand, “the whole world is open to

us.”

Others are equally enthusiastic. “The MILENA-OLGA technology

produces a more energetic syngas than anybody else in the

gasification sector,” said Paul Winstanley, a project manager in

bioenergy at the Energy Technologies Institute in the United Kingdom

who has STUDIED the system in detail but has no financial stake in

it. “The market for this is huge — people are crying out for it.”

With the system finally perfected, van der Drift and several other

former government scientists who developed MILENA-OLGA teamed up

with SYNOVA, a company founded in 2012 to take the gasification

system to market. As it turned out, it was the absolute worst time

to launch a green power company. “Clean tech was out of fashion in

the United States,” said Giffen Ott, co-founder and chief executive

officer of Synova. “People didn’t know how to do it and had gone

about it the wrong way, so everyone assumed it didn’t pay off well.”

That’s when a Palestinian refugee turned clean-tech investor named

Ibrahim AlHusseini stepped in.

Growing up near the Red Sea, AlHusseini loved nothing more than to

scuba dive, sharing his afternoons with whale sharks, octopuses,

eels and the countless fish that gathered around his favorite brain

coral — a massive growth the size of two cars.

When he returned to his favorite diving spot on the Red Sea as an

adult, he was horrified to find that the biodiversity had been

replaced by garbage. The brain coral had died, the fish were gone

and the seafloor was covered in trash. “It was just this desolate,

grey-brown spot where people had chosen to dump their stuff,” he

said.

As our global culture of convenience, consumerism and disposability

literally BURIES CITIES, landscapes and oceans in garbage, more and

more places around the world are succumbing to the same fate as

AlHusseini’s coral reef. The statistics are barely conceivable. We

produce over 3.5 MILLION TONS of solid waste each day, 10 times more

than a century ago.

Every year, garbage that winds up in landfills releases hundreds of

millions of tons of methane — a greenhouse gas up to 100 TIMES more

potent than carbon dioxide that accounts for 9 percent of global

greenhouse gas emissions. Much of the trash that doesn’t wind up in

a landfill is burned in open fires, releasing toxic chemicals, or is

dumped into the environment.

Realistically, our garbage output will not diminish anytime soon. By

2025, experts estimate that we’ll be generating 6.1 million tons per

day — almost twice what we produce now. Nor will recycling — an

industry that is CURRENTLY IN CRISIS and that even at best recovers

only A TINY FRACTION of the world’s waste — be able to save us from

rising tides of refuse.

Disposability is a notion all too familiar to AlHusseini. As a

Palestinian refugee growing up in Jordan and Saudi Arabia, he can’t

remember a time when he wasn’t keenly aware of his family’s

precarious status. In a way, he said, they themselves were

disposable people. “A refugee can acutely live out the consequences

of decisions made by others without thought or regard for the

cascading effects of those decisions,” he said.

After launching a nutraceutical company from his dorm room at the

University of Washington, by his mid-20s AlHusseini had made

millions as an entrepreneur. He became a clean-tech investor,

backing companies such as Tesla Motors, Zep Solar and Bloom Energy.

But the garbage problem continued to nag at him. So in 2013, he

founded the FULLCYCLE ENERGY FUND, an investment firm dedicated to

turning trash into clean energy. “Garbage has value, so why are we

throwing it away?” he wondered.

After being introduced to Synova by a friend familiar with his

quest, he realized MILENA-OLGA was just the answer he had been

searching for. “Brahim was there as an investor during a time that

Silicon Valley wasn’t,” said Ott.

“There’s a lot of despair about this garbage problem, but this is an

issue we can solve in our lifetimes,” AlHusseini said. “The

technology to do so is real. It’s economical. And it’s happening.”

Since then, Synova has built a 3.5-megawatt plant in Portugal and a

4.8-megawatt plant in India, where air pollution, largely from

BURNING WASTE, kills more than 2.5 MILLION people each year. “Waste

management is causing an enormous ecological disaster, but this

technology is able to convert it into the highest form of energy, so

it becomes economically attractive,” said Ramakrishna Sonde, the

executive vice president of technology and innovation at Thermax

Global, the technology company responsible for bringing MILENA-OLGA

to India as part of a clean-energy initiative. “From all points of

view, it is superior.”

Plans are in the works for plants in Costa Rica and California, and

a 30-megawatt project will open in 2019 outside Bangkok. Also in

development are mini-units that will be ideal for creating on-site,

locally generated energy for people on islands, off-grid locales or

disaster sites. “The world could use 5,000 of these projects, just

to meet garbage production now — and garbage is supposed to

quadruple in our lifetime,” AlHusseini said. “It’s an infinite

market.”

The Synova researchers calculate that, should we manage to transform

80 percent of the planet’s urban waste into power by using

conversion technologies like Synova’s, we could generate a whopping

15 percent of our residential electricity needs. “That’s not even

100 percent of garbage — or 100 percent of urban waste,” AlHusseini

pointed out.

Actually achieving anything close to that goal will require

overcoming a number of challenges, however, including steep initial

costs, especially for the first few plants. (Ott stressed that, once

up and running, the technology is cost-competitive.) But the biggest

obstacle according to AlHusseini is simply building up the momentum

needed to get investors and contractors around the world onboard.

“The joke in this industry is that everyone wants to be first in

line to fund the third project,” he said. “The more plants we have

at different scales, the easier it’s going to get.”

Geraint Evans, the bioenergy program manager at the Energy

Technologies Institute, who has no stake in Synova, agreed. “We’re

just on the cusp of commercializing these technologies,” he said.

“We need to accelerate them, but because there is no operational

history, people must be brave to be the first.”

Slowly, it’s starting to happen. In 2017, Caterpillar Ventures

joined AlHusseini in investing in Synova. According to director

Michael Young, both economics and the environment played a role in

the decision. “When you look at the proposed ideas and opportunities

to deal with our trash issue in the world today, this is absolutely

one of the leading technologies,” he said. “We see this as truly a

market opportunity to help push forward this technology.”

While syngas alone will not save the world, AlHusseini and others

believe it has an important place in a suite of technologies that

will help us tackle our most pressing environmental problems.

“Synova is a part of the solution, but so is fusion, solar, wind,

geothermal, wave technology, robotics and more,” AlHusseini said.

Given that, he encourages others in his position to consider not

just how they can generate the highest returns but how they can do

so while also making a difference. Impact investing is still a young

movement, but it is beginning to blossom and GROW as it gains

traction among major firms and sparks conferences, TED talks and

books. The paradigm shift has begun to catch on among wealthy

individuals as well, among whom bragging rights no longer hinge on

who has the biggest yacht or most spectacular jewelry but whether

their latest investment led to genuine positive change.

“I tell my story in the hopes of inspiring others to join this way

of solving problems at scale with investment capital rather than

philanthropic dollars,” AlHusseini said. “We’ll find solutions much

faster.”

This was produced by THE WORLDPOST, a partnership of the BERGGRUEN

INSTITUTE and The Washington Post.

ORIGINAL SOURCE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

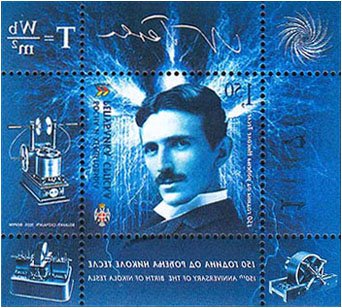

Nikola Tesla |

|